10 Things Finney Law Firm Can Do For You

Often times when people think of attorneys they think of lawsuits or criminal charges and as a result that is why they need an attorney. While attorneys are needed to help you deal with lawsuits and criminal matters that is not the end of the list of what an attorney can help you with. To help you get a better idea of how an attorney can help you I have compiled this list of 10 things that Finney Law Firm can do for you. While this list is by no means an all-inclusive list it is designed to show you areas where Finney Law Firm has the expertise to help you work through a matter and save you money or save you from legal headaches in the future.

1. Real Estate Matters

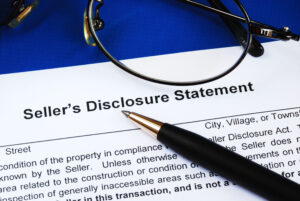

In many states in the U.S. (Ohio and Kentucky are no exceptions) attorneys are involved in many of the steps of the real estate buying and selling transaction. Often times attorneys are involved behind the scenes in reviewing contracts, legal documents, preparing title opinions and more. In certain states attorney have more hands on involvement in that any closing involving real estate is done by an attorney or under their direct supervision.

Finney Law Firm attorneys can assist individual buyers and sellers in the buying and selling process for both residential and commercial properties. As a real estate buyer you can ask an attorney to look over your offer to purchase a home to make sure it represents your best interests. Sellers may also want to hire an attorney to review any purchase offers and explain to them the requirements they will be bound by if they accept that offer. Some land purchases involve more complicated matters like mineral rights, multiple pieces of land being sold in one package, or liens by having an attorney represent  you gives you get extra protection by having the legal considerations addressed by someone trained in those matters.

you gives you get extra protection by having the legal considerations addressed by someone trained in those matters.

2. Business Planning

Are you planning on starting a new business, incorporating an existing business, or changing the corporate structure (i.e. going from an S Corporation to a C Corporation) of your current business? Many activities related to business planning should have an attorney involved in order to make sure everything is done properly. Changing your business status from a sole proprietor to a Limited Liability Company or a corporate form without doing the proper paperwork for taxes will leave you at risk with the federal and local tax authorities. While you may have unintentionally not filed some of the proper tax paperwork that will not stop any associated penalties. By working with a Finney Law Firm attorney you can be assured all your paperwork will be properly prepared and you will be fully informed as to what each document means to you in your business.

By working with an attorney to properly prepare your paperwork you have someone who is familiar with your business and will be ready, willing and able to help you should the need arise. While you can go hire an attorney at a moment’s notice to help out with legal issues, that attorney will not be as familiar with your business as one who has been working with you on an ongoing basis. For more information on the LLC form of a business see LLC see the article Why Do You Need An LLC.

3. Family Planning/Estate Planning

Marriage

Planning on getting married soon? Do you and your spouse have assets you want to keep separate in case of divorce? While the love and bliss of courtship lead you to think the relationship will last forever things and people do change. If you or your significant other own part of a family business, own your own business, have a large sum of assets from inheritance or from earnings then it is advisable to get a pre-nuptial agreement prior to getting married. A pre-nuptial agreement is a document that can protect assets for both of the people about to be married. Unless properly prepared by an  attorney and taking into account all assets a pre-nuptial agreement may not be worth much in the event of divorce. Therefore pre-marital planning should involve an attorney and the couple about to be wed. In many cases it may be best for each person to have their own attorney look over the pre-nuptial agreement to represent each person’s best interests.

attorney and taking into account all assets a pre-nuptial agreement may not be worth much in the event of divorce. Therefore pre-marital planning should involve an attorney and the couple about to be wed. In many cases it may be best for each person to have their own attorney look over the pre-nuptial agreement to represent each person’s best interests.

Family

Now if you are married and have kids there are other considerations to take into account. Those considerations mostly revolve around making sure your children and/or spouse are taken care of in the event of your passing. This is where sitting down with an estate planning attorney comes into play. An estate planning attorney will sit down with you and review your assets and your goals for your assets in case of death. This could involve setting up trusts for your spouse and/or children, guardianship arrangements for minor children, living wills, health care power of attorneys and more.

Depending on the amount of assets you have to give to your family and how you want to distribute those assets a trust may be a better option for you. A trust not only preserves your assets for your children it can also make sure you children still get their inheritance in the event your spouse later remarries. Inheritance can get quite complicated so it is best to talk with an estate planning attorney to make sure your assets are distributed the way you want them to be. For more information on wills and guardianship see my article How a Will and Trust Factor Into Your Estate Planning.

4. Legal Document/Contract Review

Have you been suddenly presented with a legal document with request for signature? Do you know what the document is meant to do and how you may be legally bound if you sign the document? If you don’t know what the language is saying or how it will impact if you sign it then by all means you should be speaking with an attorney to have them look over the document and explain to you what exactly is being asked of you. Common examples of legal documents you may be signing throughout your life include documents related to the purchase and sale of real estate, purchase or sale of a business, non-disclosure agreements for work or other purposes, waiver or release of liability paperwork, settlement documents and more.

Signing any legal document without having full understanding of what sort of obligations you may face is asking for trouble. While the language may not talk in dollars and cents terms you could end up owing plenty of money if you signed a legal document and then failed to do what was required of you under the terms of the document. An attorney will be able to review your legal document  and give you an opinion on what it is asking for and what risks you face in signing the document. Don’t sign just because the person giving it to you says it is ok, get another opinion before it is too late.

and give you an opinion on what it is asking for and what risks you face in signing the document. Don’t sign just because the person giving it to you says it is ok, get another opinion before it is too late.

5. Labor and Employment Law

Do you run a business where you are responsible for the hiring and firing of employees? Want to make sure any terminations or hiring are done correctly and there is minimal risk of you being sued for discrimination? Or maybe you are wanting to setup health plans or retirement plans for your employees and unsure of the way to go about setting up those plans?

If you answered yes to any of the above questions then you should be talking with a labor and employment law attorney who can prevent you from taking the wrong moves which end up costing you money and more. Having an effective attorney advocate at your side assures you that you can concentrate on working on your business while any legal issues are promptly dealt with for you.

6. Bankruptcy

Unsure if you can manage paying off your debts? Afraid of losing your house because you are behind on payments? Worried that your debts are impacting your health due to the constant stress? Or maybe health related expenses have hurt you financially. All of the above situations can be resolved through filing for bankruptcy. You will not know if bankruptcy is suitable for your situation until you sit down and discuss your situation with a bankruptcy attorney and learn about what filing for bankruptcy means.

In bankruptcy you are asking a bankruptcy court to set aside your debts under Chapter 7 (not all debts may be discharged) or to reorganize your debts into a more manageable payment plan under Chapter 13. Determining which Chapter will work best for you is a decision to be made in conjunction with a bankruptcy attorney.  Businesses as well as individuals are eligible to apply for bankruptcy when they are unable to pay their debts.

Businesses as well as individuals are eligible to apply for bankruptcy when they are unable to pay their debts.

7. Taxes, Taxes and more Taxes

Unaware of what taxes your need to pay for your business? Want to pay less to the Tax Man and let your family inherit more? Own a piece of property that you think you are paying too much taxes for? All of the above are matters that can be addressed by an experienced attorney at Finney Law Firm.

Business planning involves dealing with tax matters and understanding all the tax jurisdictions involved. Not only do you have to consider federal and state taxes but there are also the city, municipality, and possibly county taxes to take into account. Miss any payments to one of these tax collecting entities and your business will be at risk. By sitting down and discussing with an attorney what your business does and where it will be performing its business your attorney can better advise you as to what taxes you need to make sure are paid.

Property tax is another big issue for both residential and commercial land owners. Property tax collectors sometimes base their tax collection rates on the overall health of the real estate market in a region as opposed to your specific piece of land. Maybe you have change in situation that has lowered the value of your property but your property taxes still remain where they were before. An attorney will be able to look at your particular situation and then prepare the proper paperwork to request that your property valuation be looked at in order to get a possible downward adjustment in value thus reducing your property tax payment.

As mentioned in item 3 above a will can help you take care of your family in the event of your passing. Wills along with trusts can also shield your assets from estate taxes that can be charged to your estate. Also known as the “Death Tax”, this tax on your wealth can be minimized depending on the amount of wealth and how you deal with it now. As each individual has their own unique asset situation a consultation with an Estate Planning attorney will help you best decide how much of your assets get caught up in the “Death Tax”.

8. Litigation

When faced with litigation the last thing you want to do is ignore any requests for information nor do you want to provide answers without the guidance of an attorney in order to save money on legal bills. The answers and the way you answer pre-litigation questions (depositions and/or interrogatories) can make or break a case for you. Therefore it is in your best interest to answer these questions with an attorney present so they can stop you from answering questions you should not be answering. By having an attorney represent you in litigation from the beginning you are bringing along a valuable partner who not only will have knowledge of your case but also have the skills to defend you in a court of law. If an attorney has to be brought in later to a litigation matter it will usually be the case that they will have to spend more time in order to become fully informed of the situation which will cost you more than if you had hired an attorney at the start.

Whether you are being sued for something your business did, something an employee of yours did or you are suing someone who injured you the attorneys at Finney Law Firm have a great depth of  background and litigation experience to assist you in your litigation matter. Finney Law Firm has successfully litigated cases related to caregiver abuse of children, business transactions, personal injury cases, failure to disclose in residential and commercial real estate matters, contract disputes and more. Finney Law Firm has won a number of cases that have went before the U.S. Supreme Court.

background and litigation experience to assist you in your litigation matter. Finney Law Firm has successfully litigated cases related to caregiver abuse of children, business transactions, personal injury cases, failure to disclose in residential and commercial real estate matters, contract disputes and more. Finney Law Firm has won a number of cases that have went before the U.S. Supreme Court.

9. Personal Injury

If you have been injured by someone or someplace where the situation was preventable you may want to discuss your injuries with an attorney. Especially where you have suffered losses due to being unable to go to work, out of pocket medical bills, or other pain and suffering you may be able to be compensated for those losses. A lot of this depends on how the injury occurred and whether or not someone’s negligence leads to your injury. By talking with an attorney you get a better idea of where you stand if you do wish to seek recovery for your injuries.

10. Criminal Matters

Are you being charged with a crime? Whether that crime is driving while under the influence (DUI), reckless driving, theft or something else having an attorney represent you for the criminal trial is your right. In order to determine the severity of the charges and the amount of jail time or fines you can face you need to speak with an attorney as soon as you are able to. Facing a criminal charge is not  something you should try and handle on your own as those who will be prosecuting you are professionally trained. By having a knowledgeable and experienced attorney like those found at Finney Law Firm on your side you can be assured you will be getting the best representation possible.

something you should try and handle on your own as those who will be prosecuting you are professionally trained. By having a knowledgeable and experienced attorney like those found at Finney Law Firm on your side you can be assured you will be getting the best representation possible.

Do you have any questions about the services above?

Paul Sian is a licensed attorney in the States of Ohio and Michigan. If you feel you need the services of an attorney or have questions about any of the services named above feel free to contact me at [email protected] or via phone at 513-943-5668. Connect with me on Twitter and Facebook.